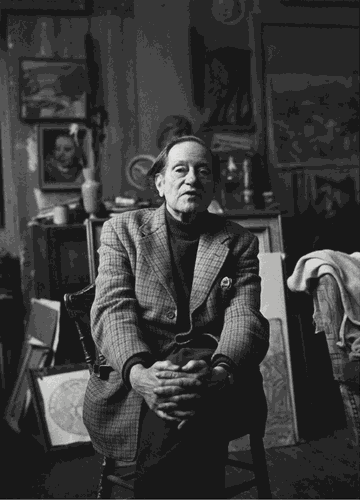

Duncan Grant Paintings for Sale1885-1978

Duncan Grant was a British artist, designer and prominent member of the Bloomsbury Group.

His father was Bartle Grant, a major in the army, and much of his early childhood was spent in India and Burma. He was a grandson of John Peter Grant, 12th Laird of Rothiemurchus and sometime Lt-Governor of Bengal. Duncan was also the first cousin twice removed of John Grant, 13th Earl of Dysart.

Grant was born in Rothiemurchus, Scotland, though much of his early childhood was spent in India and Burma. After returning to Britain permanently, he was educated at Hillbrow School, Rugby, and St. Paul's School, London. Grant showed little enthusiasm for studying, enjoying only his art classes, so was encouraged by his art teacher and his aunt, Lady Strachey, who organised drawing lessons for him. Grant’s father wanted him to join the army and turn his back on his desire to become an artist, though was eventually persuaded to allow his son to attend Westminster School of Art in 1902. This was followed by study at the Slade School, in Italy and in Paris.

He was a cousin and, for some time, a lover of Lytton Strachey. Through the Stracheys, Duncan was introduced to the Bloomsbury Group, where the economist John Maynard Keynes became another of his lovers.

Grant is best known for his painting style, which developed following the French post-impressionist exhibitions mounted in London in 1910. These were organised in part by Roger Fry, another member of the Bloomsbury Group whom Grant often worked with and was influenced by. For portraits of Fry by the Group, see the National Portrait Gallery here.

After Fry founded the Omega Workshops design house in 1913, Grant became co-director with Vanessa Bell, who was then involved with Fry. Although Grant had always been actively homosexual, a relationship with Vanessa blossomed, which was both creative and personal, and he eventually moved in with her and her two sons by her husband Clive Bell. In 1916, in support of his application for recognition as a conscientious objector, Grant joined his new lover, David Garnett, in setting up as fruit farmers in Suffolk. Both their applications were initially unsuccessful, but eventually the Central Tribunal agreed to recognise them on condition of their finding more appropriate premises. Vanessa Bell found the house named Charleston near Firle in Sussex. Relationships with Clive Bell remained amicable, and Bell stayed with them for long periods fairly often - sometimes accompanied by his own mistress, Mary Hutchinson. Their relationships were briefly summarised by his biographer Frances Spalding in the Independent, Amanda Coe in the BBC's 'Life in Squares' and recounted in many books, including this by Derek Ryan and Stephen Ross. For a summary of the interiors of the House, see Emily Senior's 2020 piece in House and Garden.

In 2020, the Charleston Trust acquired a group of erotic drawings that Grant had gifted to his friend Edward le Bas on his death.

Grant's work is included in many public collections, including that of the Courtauld, London.

In 1935 Grant was selected along with nearly 30 other prominent British artists of the day to provide works of art for the RMS Queen Mary then being built in Scotland. Grant was commissioned to provide paintings and fabrics for the first class Main Lounge. In early 1936, after his work was installed in the Lounge, directors from the Cunard Line made a walk-through inspection of the ship. When they saw what Grant had created, they immediately rejected his works and ordered it removed.

Grant is quoted in the book The Mary: The Inevitable Ship, by Neil Potter and Jack Frost:

"I was not only to paint some large murals to go over the fireplaces, but arrange for the carpets, curtains, textiles, all of which were to be chosen or designed by me. After my initial designs had been passed by the committee I worked on the actual designs for four months. I was then told the committee objected to the scale of the figures on the panels. I consented to alter these, and although it entailed considerable changes, I got a written assurance that I should not be asked to make further alterations. I carried on, and from that time my work was seen constantly by the Company's (Cunard's) representative.

When it was all ready I sent the panels to the ship to put the finishing touches to them when hanging. A few days later I received a visit from the Company's man, who told me that the Chairman had, on his own authority, turned down the panels, refusing to give any reason.

From then on, nothing went right. My carpet designs were rejected and my textiles were not required. The whole thing had taken me about a year..... I never got any reason for the rejection of my work. The company simply said they were not suitable, paid my fee, and that was that."